PUTTING YOU IN THE PICTURE

Dioramas, Cycloramas, and the Painters Philippoteaux

By Victoria Chick, contemporary figurative artist and early 19th & 20th Century Print Collector

Artist Victoria Chick discusses the history of cycloramas and the pioneering artists Henri and Paul Philippoteaux on Big Blend Radio.

Artist Victoria Chick discusses the history of cycloramas and the pioneering artists Henri and Paul Philippoteaux on Big Blend Radio.

Most of us have seen dioramas. They are frequently part of history, nature, and anthropological displays at museums. Dioramas include a background wall on which is painted the subject locale, including both sky and land. The land is represented in far distance and in middle distance. Against the wall, representing foreground, actual soil or rock is placed so it looks natural to the painted environment. Other objects, such as plants, relics, stuffed animals, etc. are placed in the foreground dirt. The whole effect gives the viewer a greater sense of place than would just a painting.

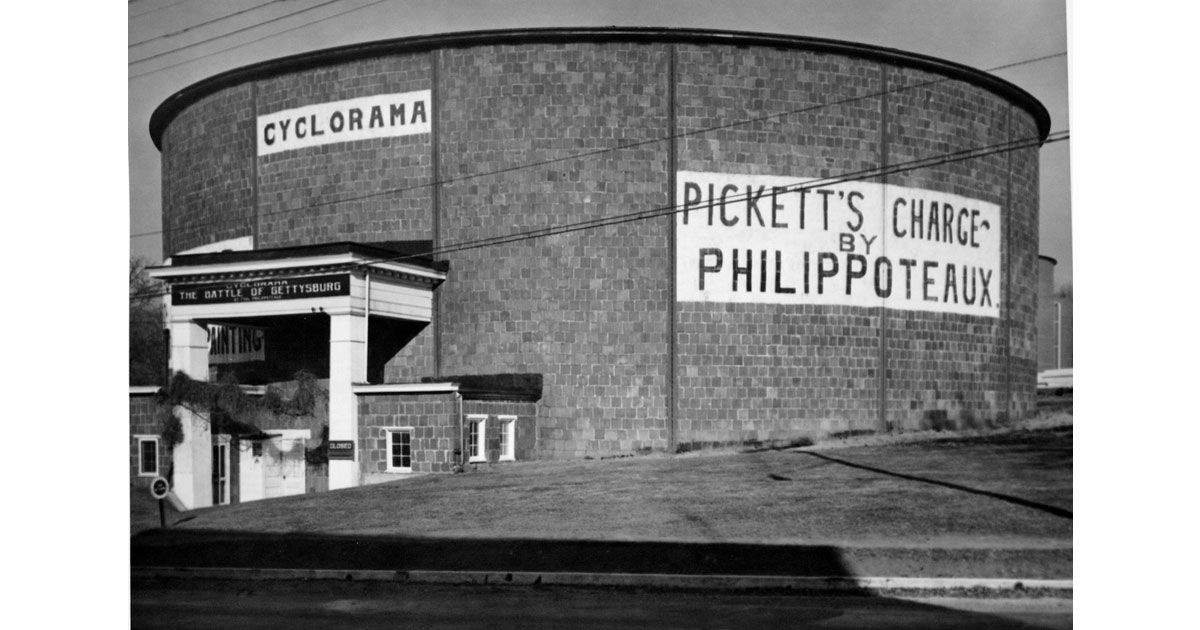

Cycloramas expand the idea of place by surrounding the viewer with a 360 degree panorama. Cycloramas became popular in the very early 19th century in Europe, from France to Russia. They were largely civic subjects done to commemorate decisive battles. They presented action and sometimes had allegorical figures. The style of painting was mostly Romantic with dramatic clouds and diagonally arranged groupings. The paintings were housed in buildings, often specially designed round buildings, so viewers could walk inside and be surrounded by the painting on the rounded wall.

The pioneering cyclorama artists were the precursors of early stage productions, like the chariot race in Ben Hur, that were so real, theatre goers often became frightened. They were the Cinerama and IMAX of their day.

Henri Philippoteaux (1815 – 1884) was born about the time cycloramas became popular. He studied art at a young age by apprenticing to other artists. As a young man he was fascinated with the challenge of cycloramas and, while he did easel paintings, gained a reputation for his work doing cycloramas in several countries. Henri Philippoteaux was the father of Paul Philippoteaux (1846 – 1923), an artist best known for the 1883 cyclorama depicting “Pickett’s Charge up Cemetery Ridge” at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. His father worked with him on this project during the early stages but died before it was completed. Paul Philippoteaux was mentored by his father but also studied at the College Henri IV and the Ecole des Beaux Artes where he received classical training and became familiar with the Classical and Romantic styles preferred for painting dramatic historical subjects at that period in time.

The Philippoteaux father and son duo had gained such a good reputation for cycloramas in Europe, they were contacted by a group of Chicago businessmen to depict the Battle of Gettysburg.

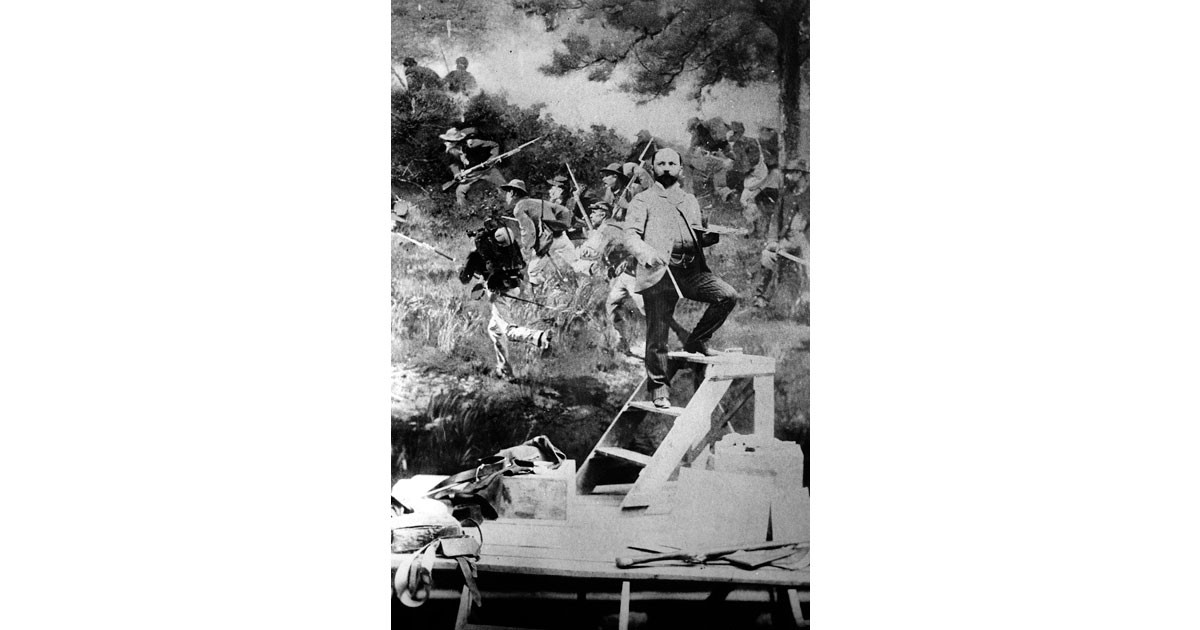

The Philippoteaux’s always did complex research for their cycloramas. The Gettysburg cyclorama involved research interviews with survivors of the Battle. Since photography was available in the 1870s, one of their assistants took a photo series from atop a platform especially built at the Battle site. The photos were set up sequentially after being printed, so an accurate 360 degree landscape location could be used for reference during the drawing process. Interviews with surviving members of the military gave first-hand accounts of the action that took place during the Battle.

One of the difficulties of painting a large scale canvas is maintaining color relationships and brushwork so the painting looks unified. This was doubly difficult with many assistants. Using a limited palette and premixing large amounts of colors would help. It would be probable the assistants helped draw and do underpainting in neutral chiaroscuro tones while the finished work was completed by Paul Philippoteaux. However it was done, it was a monumental project taking the better part of two years to complete.

Put together, the canvases were one hundred feet long and weighed six tons. Paul Philippoteaux decided, on the Gettysburg cycloramas, to include the physical foreground elements of diorama. This was a first for a cyclorama and the added realism contributed to the amazement of the great crowds that came to view it. Even more amazing is that the Philippoteaux team actually did four versions of this cyclorama, two of which survived. One version, shown originally in Philadelphia, went to Denver, where it was exhibited for a time, then reportedly was cut up and used to make tents for a Shoshone Indian Reservation. However, this is open to conjecture. The first version went to Chicago where it was exhibited with great acclaim. Its realism was such that Civil War veterans, who saw it, reportedly wept at the sight. This version was lost but rediscovered in 1965 and sold to a group of investors and has been stored since then. Its estimated value is 5.5 million dollars. No records exist for the fate of the third version.

The fourth version has a checkered past. It was exhibited in Boston from 1884-1891 and, according to a newspaper report, was well received. It was moved to Gettysburg National Military Park where ground was broken in 1912 for a special building to commemorate the end of the Civil War. However, the building was unheated, leaky, and the painting began to deteriorate. The National Park Service purchased the painting in 1942. It went through restoration in 1962. The Park Service moved it to Zeigler’s Grove near the then Gettysburg Visitor’s Center, and it was placed in a building designed by architect Richard Neutra where it was on display until 2005.

Today, after another restoration, the Cyclorama Exhibition is housed in a new facility, the Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center.

Victoria Chick is the founder of the Cow Trail Art Studio in southwest New Mexico. She received a B.A. in Art from the University of Missouri at Kansas City and awarded an M.F.A. in Painting from Kent State University in Ohio. Visit her website at www.ArtistVictoriaChick.com

|

|

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.